Saturday, December 3, 2016

Elizabeth MacDonald, Pearl Harbor reporter

REPORTER ELIZABETH MacDonald, on assignment in Honolulu, was in bed on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, listening to a radio broadcast of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Suddenly an announcer cut in. “The islands are under attack,” he said. “This is the real McCoy.” Elizabeth didn’t think it was the real anything; she was sure it was just another army maneuver. But a few minutes later, she received a call from her photographer at Scripps Howard News Service. He wasn’t sure which country was doing the bombing, Germany or Japan, but he did know that the US naval base at Pearl Harbor was under attack.

During the first half of their drive to Pearl Harbor, Elizabeth and the photographer didn’t notice anything unusual; it was a typically quiet Sunday morning. But when they got closer, Elizabeth saw something shocking. Reporting later, she described it as “a formation of black planes diving straight into the ocean off Pearl Harbor. The blue sky was punctured with anti-aircraft smoke puffs.” It was the second wave of Japanese bombers. Looking over her shoulder, Elizabeth suddenly saw “a rooftop fly into the air.”

She wrote that she now understood “that numb terror that all of London has known for months. It is the terror of not being able to do anything but fall on your stomach and hope the bomb won’t land on you.”

The Japanese had targeted the battleships in Pearl Harbor and the nearby airfields, not civilians. But because the Japanese destroyed most of the US planes before they could get airborne and do battle, frantic US military personnel on the ground tried to shoot the Japanese down with anti-aircraft guns. Some of their misfired ammunition destroyed buildings, killed 68 civilians, and wounded 35.

Elizabeth was not allowed near Pearl Harbor—the US military did not want female journalists on the front lines of military action—so she focused instead on the civilian casualties in the area and the desperate attempts to save them.

“The blood-soaked drivers returned with stories of streets ripped up, houses burned, twisted shrapnel and charred bodies of children,” she wrote. In the morgue, Elizabeth saw bodies “laid on slabs in the grotesque positions in which they had died. Fear contorted their faces.”

As Elizabeth watched firefighters bring victims inside—some of them with the acronym DOA (dead on arrival) marked on their foreheads—she wrote that life had suddenly become “blood and the fear of death—and death itself. . . . In the emergency room . . . doctors calmly continued to treat the victims of this new war. Interns were taping up windows to prevent them from crashing into the emergency area as bombs fell and the dead and wounded continued to arrive.”

When Elizabeth left the emergency room and returned to Honolulu, she saw that many familiar shops had burned down. After dusk, she described “the all-night horror of attack in the dark. Sirens shrieking, sharp, crackling police reports and the tension of a city wrapped in fear.”

Excerpts from "Elizabeth MacDonald: Pearl Harbor Reporter and OSS Agent" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Friday, October 7, 2016

The Bataan-Corregidor nurses on their way home

US nurses, February 12, 1945, recently released from Santo Tomas internment camp

Photo credit: John Tewell

On July 2, 1942, the nurses were imprisoned in the Santo Tomas internment camp in Manila, where they tried, as much as possible, to help the other prisoners as they all struggled to survive on starvation rations.

Finally, on the evening of February 3, 1945, US troops liberated Santo Tomas. They came too late for many of the prisoners, who had by then died of ailments related to undernourishment. All of the Bataan-Corregidor nurses survived.

On Sunday, February 11, 1945, American lieutenant colonel Nola Forrest told the gaunt, exhausted, but elated nurses to be ready for departure on the following morning. She also mentioned that US intelligence officials, who realized these women had never been trained for combat nursing, were eager to debrief them. “You’re the first [US military] women to have served under actual combat conditions,” she said. “Whatever tips you have on how you survived could be of great help to others.”

All the nurses would be promoted to a higher military rank, Forrest said, and would receive the Presidential Citation and a Bronze Star.

Excerpt from "Denny Williams: Nurse under Fire" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

The Vocal Orchestra of the Palembang Internment Camp

The Colijn sisters, Dutch East Indies, 1939.

Left to right: Antoinette, Helen, Alette.

(Both Antoinette and Alette sang in the vocal orchestra).

Photo credit: Song of Survival by Helen Colijn.

Then Helen saw the word ORCHESTRA scratched in large letters in the dirt. Orchestra? She knew there were no real instruments in camp. Had she generated excitement for a performance played on crude homemade instruments?

They would all soon find out. A few minutes later, 30 women, each holding a piece of paper in one hand and a stool in the other, filed out of the main kitchen to face the audience. Children sat in front, while many of the adults, including Helen, stood.

Then Margaret Dryburgh spoke. “This evening,” she said, “we are asking you to listen to something quite new, we are sure: a choir of women’s voices trying to reproduce some of the well-known music usually given by an orchestra or a pianist.” The singers, she said, would sit on their stools just like orchestra performers, in order to conserve their energy.

Then she took her place among the singers. Norah Chambers stood in front of the performers. She raised her hands. The choir began to sing, in four-part harmony, Dvorak’s “Largo” from the New World Symphony.

(Sheet music copied by Norah Chambers for the vocal orchestra.)

“Huu, huu.” Helen heard a new sound, “the ugly raw voice of an angry guard,” coming up behind her. Surely Norah could hear it too. But she didn’t stop directing the music.

“Huu, huu.” The angry guard, his bayonet fixed on his rifle, passed through the standing audience. Soon Helen could only see the tip of his bayonet.

The music continued. The angry voice did not. Helen craned her neck: she could no longer see the bayonet. Had the guard put down his weapon? Was he also mesmerized by the beautiful music? Apparently so. “As the Largo moved toward a great, glorious crescendo,” Helen would write later, “the guard remained as still as we for the rest of the concert."

Excerpt from "Helen Colijn: Rising Above" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Click here for more about the vocal orchestra.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Jane Kendeigh lands on Iwo Jima

Jane Kendeigh attempts to comfort wounded marine William Wyckoff.

Iwo Jima, March 6, 1945.

Credit: US Navy Bureau of Medicine & Surgery Library & Archives

"Although the plane was high enough to be clear of the US bombardment, it was certainly visible to the Japanese snipers below. Jane knew that Japanese anti-aircraft guns on the island had already shot down US carrier planes. One of those guns might still be in action. But an anti-aircraft gun wouldn’t be necessary to take them down; a single bullet hitting the fuel tank would cause the plane to explode. So Jane and the others were relieved when the plane finally swished past the highest point on the island—Mount Suribachi—and settled in for a landing.

Jane’s destination was beside the airstrip: a small sandbagged hospital tent. The roar of guns and artillery was so loud, Jane and Silas could barely hear one another speaking as they hurried inside. There they found doctors and male medics working frantically to save lives in rough conditions. The stretcher-bearers carried wounded men out of the tent and lined them up near the waiting plane. Jane spoke comfortingly to each man, if he was conscious, and checked him as he went aboard.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant DeWitt asked the medics in the tent about the previous plane, the one he’d missed. They told him it was due in very soon; the pilot had lost his way.

This delay meant that Jane Kendeigh had suddenly become front-page news: the first navy flight nurse to land on Iwo Jima, the first navy flight nurse to step onto a World War II Pacific battlefield. Lieutenant DeWitt’s photograph of her speaking to William was transmitted to the United States, where it appeared in nearly every newspaper in the nation."

Excerpt from "Jane Kendeigh: Navy Flight Nurse" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Monday, August 29, 2016

Helen Colijn: Digging Graves in the Internment Camp

Helen (center) and her sisters.

The Dutch East Indies, 1939.

Credit: Song of Survival

THE JAPANESE GUARD held up two fingers. Only two graves. A few days earlier it had been eight.

Helen Colijn, a Dutch teenager, along with three other prisoners, had volunteered for grave duty. Sometimes digging graves didn’t seem as depressing as living in the filthy internment camp with all of the starving, sick, and dying women.

Helen’s view of death had changed drastically during her imprisonment. It was no longer a shock, and barely a sorrow. It occurred nearly every day. Few of the surviving prisoners still had the energy to grieve.

But Helen could do something to help: she could dig. The guards wouldn’t do it, so it was up to the prisoners. She wished the guards would at least give them better digging tools...

From "Helen Colijn: Rising Above" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Monday, August 22, 2016

Helen Colijn: The War is Over

"On August 24, 1945, the prisoners who were not bedridden were summoned to a spot outside the guardhouse. The camp commander told them the war was over. He didn’t tell them who had won.

The following day, the women began to receive items they’d previously been told were unavailable: food, medicine, blankets, bandages, mosquito nets, towels. Many weak prisoners continued to die, and all of them had to carry on in the squalor of the camp. But they were no longer starving. And they knew help was on the way.

On September 7, 1945, Dutch paratroopers entered the camp. They said 'they had never seen such awful conditions' [in the camps they’d been liberating] and were amazed that anyone could live like this.'"

From "Helen Colijn: Rising Above" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

The following day, the women began to receive items they’d previously been told were unavailable: food, medicine, blankets, bandages, mosquito nets, towels. Many weak prisoners continued to die, and all of them had to carry on in the squalor of the camp. But they were no longer starving. And they knew help was on the way.

On September 7, 1945, Dutch paratroopers entered the camp. They said 'they had never seen such awful conditions' [in the camps they’d been liberating] and were amazed that anyone could live like this.'"

From "Helen Colijn: Rising Above" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Thursday, August 18, 2016

Maria Rosa Henson: "Don't be ashamed."

"Then one morning in 1992, she heard a woman on the radio discussing the topic of so-called comfort women who had been forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese government during the war.

Maria Rosa began to shake uncontrollably. She heard the woman on the radio discuss something called the Task Force on Filipino Comfort Women. 'Don’t be ashamed,' the woman said. 'Being a sex slave is not your fault. It is the responsibility of the Japanese Imperial Army. Stand up and fight for your rights.'

'My heart was beating very fast,' Maria wrote later of that moment. 'I asked myself whether I should expose my ordeal. What if my children and relatives found me dirty and repulsive?'

She didn’t call in, but she listened to that radio station every day. A few weeks later, she heard a similar announcement. She began to weep. At that moment, her daughter Rosario walked in. Maria Rosa finally told her the truth.

Rosario helped her get in touch with the task force. Maria Rosa was interviewed on tape, Rosario at her side. It was extremely difficult, but also a relief. 'I felt like a heavy weight had been removed from my shoulders,' she wrote later, 'as if thorns had been pulled out of my grieving heart. I felt I had recovered my long-lost strength and self-esteem.'

Maria Rosa was the first Filipina comfort woman to break her silence..."

From "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Maria Rosa began to shake uncontrollably. She heard the woman on the radio discuss something called the Task Force on Filipino Comfort Women. 'Don’t be ashamed,' the woman said. 'Being a sex slave is not your fault. It is the responsibility of the Japanese Imperial Army. Stand up and fight for your rights.'

'My heart was beating very fast,' Maria wrote later of that moment. 'I asked myself whether I should expose my ordeal. What if my children and relatives found me dirty and repulsive?'

She didn’t call in, but she listened to that radio station every day. A few weeks later, she heard a similar announcement. She began to weep. At that moment, her daughter Rosario walked in. Maria Rosa finally told her the truth.

Rosario helped her get in touch with the task force. Maria Rosa was interviewed on tape, Rosario at her side. It was extremely difficult, but also a relief. 'I felt like a heavy weight had been removed from my shoulders,' she wrote later, 'as if thorns had been pulled out of my grieving heart. I felt I had recovered my long-lost strength and self-esteem.'

Maria Rosa was the first Filipina comfort woman to break her silence..."

From "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Maria Rosa Henson: Filipina "Comfort Woman"

"At gunpoint, the sentry led Maria Rosa to the second floor of a Japanese garrison. There she saw six other women. She was led a small room with a bamboo bed and no door, only a curtain.

On the following day, one that she would later describe as “hell,” Maria Rosa discovered why she and the other women had been brought to the garrison. A Japanese soldier entered her room. He pointed a bayonet at her chest. She was terrified; she thought he was going to kill her. Instead, he slashed her dress open. Then he raped her.

Twelve more soldiers followed..."

From "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

On the following day, one that she would later describe as “hell,” Maria Rosa discovered why she and the other women had been brought to the garrison. A Japanese soldier entered her room. He pointed a bayonet at her chest. She was terrified; she thought he was going to kill her. Instead, he slashed her dress open. Then he raped her.

Twelve more soldiers followed..."

From "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Saturday, August 6, 2016

Margaret Utinsky learns of Jack's death

"Margaret wondered if Jack was receiving any of these supplies. She hadn’t heard anything from or about him yet. But she was willing to do anything just in case her actions might be helping him. “Risks did not seem too dangerous,” she wrote later, “when I thought of him inside those fences.”

In December, Margaret heard that the surviving men were being moved to a new prison complex, consisting of three camps, located near Cabanatuan City. By way of two Filipino contacts in the Miss U Network, Margaret started communicating with an American officer in the prison named Colonel Mack. She sent him a note, asking if he knew anything about the fate of a Jack Utinsky. A note came back:

Dear Miss U:

You have many friends in this place. . . . I am deeply sorry that I have to tell you what I found out. Your husband died here on August 6, 1942. He is buried here in the prison graveyard. . . .

You will be told that he died of tuberculosis. That is not true. The men say that he actually died of starvation. A little more food and medicine, which they would not give him here, might have saved him.

This is terrible news for you, who have, with your unselfish work, been able to save so many others. All of us will always owe you a debt that we can never pay for what you have done.

I do want to say to you that this place is far more dangerous for your work than Camp O’Donnell was. Do not take risks that you took there. If you never do another thing you already have done more than any living person to help our men. My sympathy goes out to you in your grief. God bless you in all you do.

Sincerely yours, Edward Mack,

Lt. Colonel, U.S. Army

Jack had starved to death. Margaret blamed herself. “If he could have received just a little of the food I had given to others,” she wrote later, “he might be alive. If I had found him four months sooner, he might be alive..."

Excerpt from "Margaret Utinsky: The Miss U Network" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater: 15 Stories of Resistance, Rescue, Sabotage, and Survival.

In December, Margaret heard that the surviving men were being moved to a new prison complex, consisting of three camps, located near Cabanatuan City. By way of two Filipino contacts in the Miss U Network, Margaret started communicating with an American officer in the prison named Colonel Mack. She sent him a note, asking if he knew anything about the fate of a Jack Utinsky. A note came back:

Dear Miss U:

You have many friends in this place. . . . I am deeply sorry that I have to tell you what I found out. Your husband died here on August 6, 1942. He is buried here in the prison graveyard. . . .

You will be told that he died of tuberculosis. That is not true. The men say that he actually died of starvation. A little more food and medicine, which they would not give him here, might have saved him.

This is terrible news for you, who have, with your unselfish work, been able to save so many others. All of us will always owe you a debt that we can never pay for what you have done.

I do want to say to you that this place is far more dangerous for your work than Camp O’Donnell was. Do not take risks that you took there. If you never do another thing you already have done more than any living person to help our men. My sympathy goes out to you in your grief. God bless you in all you do.

Sincerely yours, Edward Mack,

Lt. Colonel, U.S. Army

Jack had starved to death. Margaret blamed herself. “If he could have received just a little of the food I had given to others,” she wrote later, “he might be alive. If I had found him four months sooner, he might be alive..."

Camp O'Donnell burial detail

Excerpt from "Margaret Utinsky: The Miss U Network" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater: 15 Stories of Resistance, Rescue, Sabotage, and Survival.

Saturday, July 30, 2016

Minnie Vautrin: American Hero at the Nanking Massacre

"Minnie spent most of her time running from one end of the campus to another, trying to stay one step ahead of the raping, looting soldiers. Her commanding presence was enough to make some of them quit, but others, she wrote, would look at her “with a dagger in their eyes and some times a dagger in their hands.” One Japanese soldier became so angry with Minnie when she tried to prevent a looting, he pointed a gun at her. Another slapped her.

Meanwhile, the refugees continued to flood into Ginling, “with horror written on their faces,” wrote Minnie, and relating “stories of tragedies such as I have never heard before.”

Minnie was desperate. She decided to visit the Japanese embassy in Nanking to see if anyone there would help her.

A sympathetic embassy clerk wrote two official letters ordering the soldiers to leave the women of Ginling alone. He also gave Minnie some official “proclamations” to post on the outside of Ginling’s walls, declaring the campus off-limits to Japanese soldiers.

He even arranged for Minnie to be driven home in the embassy car. The driver told Minnie, “the only thing that had saved the Chinese people from utter destruction” were the “handful of foreigners” running Nanking’s safety zone. Minnie was glad to be making a difference, of course, but the driver’s words filled her with a certain despair: “What would it be like,” she wrote, “if there were no check on this terrible devastation and cruelty?”

On the following day, she tested the power of the letters..."

From "Minnie Vautrin: American Hero at the Nanking Massacre" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Meanwhile, the refugees continued to flood into Ginling, “with horror written on their faces,” wrote Minnie, and relating “stories of tragedies such as I have never heard before.”

Minnie was desperate. She decided to visit the Japanese embassy in Nanking to see if anyone there would help her.

A sympathetic embassy clerk wrote two official letters ordering the soldiers to leave the women of Ginling alone. He also gave Minnie some official “proclamations” to post on the outside of Ginling’s walls, declaring the campus off-limits to Japanese soldiers.

He even arranged for Minnie to be driven home in the embassy car. The driver told Minnie, “the only thing that had saved the Chinese people from utter destruction” were the “handful of foreigners” running Nanking’s safety zone. Minnie was glad to be making a difference, of course, but the driver’s words filled her with a certain despair: “What would it be like,” she wrote, “if there were no check on this terrible devastation and cruelty?”

On the following day, she tested the power of the letters..."

From "Minnie Vautrin: American Hero at the Nanking Massacre" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Tuesday, July 26, 2016

Claire Phillips learns of Phil's death at Cabanatuan

Claire Phillips

On October 17, 1942, Claire opened a nightclub located near Manila’s busy harbor. She named it the Tsubaki Club after a rare Japanese flower. Her opening night was a huge success, and she looked forward to earning more Japanese money to fund resistance efforts. But her mind was always on Phil.

The following day, Claire felt the time was right to get an update on him. She called on Father Theodore Buttenbruch, a fellow resister and German priest who the Japanese were allowing to visit Cabanatuan under careful supervision. She asked Father Buttenbruch if he would carry a message to Phil.

Two weeks later, the priest called Claire to his office. He had lists of POWs who had died at Cabanatuan. Phil had died, he said, on July 26, 1942.

Sketch made by a survivor of Cabanatuan

Library of Congress

A few days later, she received a sympathy note from Chaplain Frank Tiffany, who lived at Cabanatuan. Although Phil’s death certificate stated that he had died of malaria, Chaplain Tiffany told Claire the underlying reason for Phil’s death was malnutrition.

'But I beg of you,' he continued, 'not to forget the ones that are left. They are dying by the hundreds.'

Cabanatuan survivors, 1945

National Archives

Claire was heartbroken. It took her several days to recover enough to return to work. But when she did, the circumstances of Phil’s death gave her an additional motivation to keep the Tsubaki Club successful. She also became more motivated to engage in her own form of espionage.

The Tsubaki Club regularly entertained powerful Japanese civilians and military men who passed through Manila..."

From "Claire Phillips: Manila Agent" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Monday, July 25, 2016

Vivian Bullwinkel and Private Kinsley: Surrender at Muntok

Vivian Bullwinkel shortly before she left for Singapore

"Vivian decided they should take a chance and surrender to the Japanese at Muntok headquarters, a few miles away. Kinsley immediately agreed, saying 'If it comes to the worst I hope the Japs do a better job of it this time.'

"They began the long, exhausting trip to Muntok, Kinsley dividing his weight between Vivian and a cane.

When they reached the headquarters, they had a few moments to say good-bye.

'I want you to know that I admire you very much,' Vivian whispered to Kinsley, 'and I feel a great pride in having had you as a companion.'

'I would never have made it thus far,” Kinsley replied, 'if it hadn’t been for you. I used to look at you and wonder, what with everything that happened to you, where you got your strength from to go on. You set the example, you made me determined to be like you.'

A car pulled up to take Kinsley away..."

From "Vivian Bullwinkel: Sole Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Vivian Bullwinkel: Banka Island

Vivian Bullwinkel shortly before she left Australia for Singapore

National Library of Australia

Copyright: Bruce Howard

"The Japanese soldiers came back, each of them cleaning his bayonet with a cloth. The British servicemen were not with them.

“Bully,” one nurse said, addressing Vivian, “They’ve murdered them all!”

Vivian was silent.

“It’s true then, they aren’t taking prisoners,” said another nurse.

The Japanese officer said something to his soldiers. They surrounded the 22 Australian nurses. They prodded the nurses with their bayonets until the women had formed a line into the water. Two wounded nurses had to be half carried there by their companions.

It seemed impossible to Vivian that a mass slaughter was about to occur in this beautiful setting. She kept asking herself why. And what right did the Japanese have to kill them?

But she said nothing aloud. None of the nurses did. Except for the sound of the water hitting their thighs, the beach was silent. Vivian, sad to think her mother would never learn what happened to her, suddenly felt peaceful when she realized she would soon see her deceased father. She wanted to communicate her new emotion to the other nurses. She turned and smiled at them. They returned her smile 'in a strange and beautiful way.'

They had obviously found their own ways to cope during these last terrible moments.

Then Vivian heard the whispered voice of their matron, Irene Drummond, 'Chin up girls, I’m proud of you and I love you all.'

Irene Drummond

From "Vivian Bullwinkel: Sole Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

The Kempeitai visit Elizabeth Choy

"The Kempeitai mistakenly suspected that this successful sabotage—code-named Operation Jaywick by the special forces—was somehow connected to the British prisoners in the Changi prison. They made a thorough search and discovered multiple radio sets hidden carefully under prison chairs. The British prisoners had not only been physically hungry but were also starved for news outside of Japanese-controlled propaganda.

Fifty-seven civilians were taken into Kempeitai custody, interrogated, and brutally tortured. Fifteen were tortured to death. These arrests and interrogations would forever be remembered in Singapore as the Double Tenth Incident, so named because they began on October 10, an important date in the founding of China’s Republic.

Where had the prisoners obtained their radio sets? The Kempeitai were determined to find out. During one particularly brutal interrogation, one of the internees who had been found with a radio admitted he had obtained its parts from the Choys. While passing notes and food, Elizabeth and her husband had also passed radio parts. They rarely knew exactly what was in each package. And they never asked.

On the following day, a car stopped outside the tuck shop. A Kempeitai officer asked Elizabeth’s husband, Khun Heng, if he would get into the car: he wasn’t familiar with the area, the officer said, and needed help with directions.

Khun Heng agreed to help. He didn’t return.

Alarmed, Elizabeth traveled to Kempeitai headquarters with a blanket and extra clothing, pleading with the officers to give the items to her husband.

The officers told Elizabeth they didn’t know where he was.

But three weeks later, some Kempeitai officers unexpectedly visited the tuck shop and offered to take Elizabeth to see Khun Heng..."

From "Elizabeth Choy: Justice Will Triumph" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Maria Rosa Henson: Guerrilla Courier

"One day Pinatubo asked Maria Rosa if she wanted to join the Huk. She was glad to be offered a chance to fight back against the Japanese. After joining, she was assigned to carry messages and collect food, medicine, and clothing from people sympathetic to the Huk guerrillas.

Once, while on her way to collect medicine and deliver a message, Maria Rosa saw some Japanese soldiers a long way off. She quickly ate the message. The soldiers suspected nothing and let her pass. But Maria Rosa knew she’d had a close call. Those suspected of working with the Huk were always taken to the local Japanese garrison, where they were tortured for information before being killed. So the Huk held their meetings in different neighborhoods in order to avoid detection. And as Maria Rosa went from village to village for the Huk, she was careful to never disclose her real identity: her code name was Bayang.

Maria Rosa’s work gave her a deep sense of purpose. Yet she was continually haunted by the memory of the rapes, especially when she sang the following lines of a song with her comrades:

They should be vanquished, the fascist Japanese,

The scourge of our race.

They seized our possessions and raped our women.

After singing those words, Maria Rosa would always whisper to herself, 'I am one of those women.'"

Excerpt from "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Once, while on her way to collect medicine and deliver a message, Maria Rosa saw some Japanese soldiers a long way off. She quickly ate the message. The soldiers suspected nothing and let her pass. But Maria Rosa knew she’d had a close call. Those suspected of working with the Huk were always taken to the local Japanese garrison, where they were tortured for information before being killed. So the Huk held their meetings in different neighborhoods in order to avoid detection. And as Maria Rosa went from village to village for the Huk, she was careful to never disclose her real identity: her code name was Bayang.

Maria Rosa’s work gave her a deep sense of purpose. Yet she was continually haunted by the memory of the rapes, especially when she sang the following lines of a song with her comrades:

They should be vanquished, the fascist Japanese,

The scourge of our race.

They seized our possessions and raped our women.

After singing those words, Maria Rosa would always whisper to herself, 'I am one of those women.'"

Excerpt from "Maria Rosa Henson: Rape Survivor" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Denny Williams: The Surrender at Corregidor

A portion of the bedsheet signed by the nurses at Corregidor on May 6, 1942.

Denny Williams’s name is in the middle of the third column.

AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Archival Repository

"IT WAS THE MORNING of May 6, 1942. In a few hours, the US Army stationed on the Philippine island of Corregidor would surrender to the army of Imperial Japan.

But the fighting men would not be the only ones involved in this surrender. Along with them were female nurses, some of them civilians but most of them official members of the US Army. None of these women had been trained in combat nursing and yet they had endured months of just that. Now they awaited their fate. They were all too aware of the horrors the Japanese army inflicted on Chinese women four and a half years earlier during the Nanking Massacre. Tomorrow they would be facing the same enemy. Were they now living their last hours? If so, would anyone ever know what they had endured during the past grueling months?

They wanted to leave proof that they had been alive before meeting the Japanese face-to-face. One of them tore a large square from a bedsheet. Another wrote the following words at the top: “Members of the Army Nurse Corps and Civilian women who were in the Malinta Tunnel when Corregidor fell.” Then 69 women signed their names. One of them was Denny Williams."

Opening paragraphs from "Denny Williams: Nurse under Fire" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Bataan/Corregidor nurses leaving Santo Tomas prison in 1945

AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Archival Repository

Gladys Aylward: A Price on Her Head

Gladys Aylward

"Soon 100 children were on their way with one of Gladys’s trusted friends. But before a month had passed, 100 more orphans had found their way to the mission.

One day, a Chinese general sent Gladys a message: the Japanese were approaching Yangcheng in large numbers. The Chinese army was retreating. He wanted Gladys to come with them. They would care for the children on the way.

Although Gladys was concerned for the children’s safety, she rarely feared for her own. The children left with the general and his men. Gladys remained at Yangcheng.

Two nights after their departure, a Chinese soldier knocked on her door, telling Gladys he had been sent back to once more persuade her to leave.

“Whether you leave with us nor not, you must leave. We have received certain information.”

“What information?” Gladys asked.

“The Japanese have put a price on your head.”

“You are just saying this to make me leave,” Gladys replied.

He wasn’t. The soldier pulled a paper out of his pocket, one of many, he said, that had been found posted on a nearby city wall. The paper listed three names and stated the following: “Any person giving information which will lead to the capture, alive or dead, of the above mentioned, will receive [a large sum of money] from the Japanese High Command.” One of the names listed on the poster was “Ai-weh-deh,” Gladys’s official Chinese name.

Why did this missionary have a price on her head?"

From "Gladys Aylward: All China is a Battlefield" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Friday, July 22, 2016

Sybil Kathigasu and the Guerrilla Fighters

Photo credit: Media Masters Publishing, Malaya

"The occupying Japanese administration forced the Malayans to abandon Western culture and replace it with Japanese. Malayans had their homes searched regularly to ensure no one still owned pictures of the British royal family, the flags of any Allied nations, or even American record albums.

The Japanese were also obsessed with persecuting Papan’s large Chinese population. They would randomly round them up and make them stand for hours—sometimes days—in the hot sun without food or water. Many collapsed, and some died.

A guerrilla movement was born out of this persecution. The Chinese guerrillas near Papan fought the Japanese occupation by assassinating Malayan collaborators who were betraying their fellow Malayans to the Japanese. Large Japanese offensives would then be launched against the guerrillas. But when collaborators continued to meet their doom from hidden assassins, everyone knew the guerrillas were, in the main, alive and well.

One day, they asked Sybil for help.

“It’s the guerillas, Mrs. K,” said Moru, a young Chinese man acquainted with her. “Some of them are sick and wounded, and need medicines. They knew you don’t like the Japs. Will you help?”

Sybil knew the Japanese penalty for helping a guerrilla was severe..."

Excerpt from "Sybil Kathigasu: 'This Was War'" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Minnie Vautrin

Minnie Vautrin as a young woman

(www.discipleshistory.org)

"IN DECEMBER 1937, Nanking was a city in flight. Its streets were jammed with the last major flood of civilians who had the means to leave the war-torn city. Half the original population was now gone. Most of the remaining 500,000 civilians were there only because they couldn’t afford transportation or had nowhere else to go.

But there was one small group of foreigners in Nanking—Americans and Europeans—who had stayed deliberately. They were the members of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, which referred to an approximate three-mile area in the city designed to be a wartime refuge for civilians. Women and children were to be housed within the safety zone at Ginling Women’s College. Its president was an American woman named Minnie Vautrin."

Opening paragraphs of Minnie Vautrin: American Hero at the Nanking Massacre from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Margaret Utinsky: Hiding From the Japanese

Margaret Utinsky

"MARGARET UTINSKY PEERED out the window of her second-floor apartment. On the street below, Japanese officers questioned everyone who passed by. They were rounding up “enemy aliens”: British and American citizens. Margaret had no intention of being among them. She could afford to wait a long time; her apartment was stocked with food and medical supplies provided by personnel working at the US military bases in Manila...

Margaret, a Red Cross nurse by day and the operator of a servicemen’s canteen by night, had taken taxi-loads of those supplies, hoping to open her canteen again when the fighting was over. She wanted to be of help, especially to her husband, Jack, a civil engineer with the US military in Manila who had urged Margaret to evacuate with the other military wives when the Japanese first attacked. Margaret had refused. Later, when Manila was declared an open city and Jack was ordered to pull back to the Bataan Peninsula with the rest of the military, Margaret refused his urgent suggestion to stay at the local hotel with the other American and British civilians; she assumed—correctly—that the Japanese would round them up and force them into an internment camp. And Margaret didn’t see how she could be of any use to Jack in an internment camp.

After the Japanese searched through the first floor of the apartment building and found all the apartments vacated, they didn’t bother checking the second floor..."

Opening paragraphs of "Margaret Utinsky: The Miss U Network" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

Claire Phillips and the Tsubaki Club's Opening Night

Claire Phillips, aka Dorothy Fuentes

The guests were treated to one dazzling dance production after another. For the finale, the elegant owner appeared alone on the dance floor. Dressed in a long, glittering white evening gown, Dorothy Fuentes sang beautifully for her guests. When she was finished, the crowd jumped to their feet in a thunderous standing ovation.

When the last guests had left, Dorothy checked the overflowing cash box. She knew that the Tsubaki Club was now the most popular spot for the Japanese in Manila. Her plan would work. She wrote the following note: 'Our new show was a sell out. You can count on regular backing. Standing by for orders and assignments.'

She was about to sign it, then stopped. She couldn’t use her name; it was too risky. But what could she use as an alias? She thought for a moment about how she always stashed money in her bra. She signed the note, 'High Pockets.'"

Opening paragraphs of "Claire Phillips: Manila Agent" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Saturday, June 18, 2016

Yay Panlilio meets guerrilla leader Marcos Villa Agustin, aka Marking

"The mountains, Yay , knew, were filled with bands of Filipino guerrilla fighters. She would have liked to join them but quickly dismissed the idea. They were constantly on the run from the Japanese, and she knew she wouldn’t be able to keep up with them: the year before, while covering a story, she had broken her leg in a serious auto accident, and her bone had not been set properly. She also had a heart condition.

Plus she was a woman. How could she live among hundreds, perhaps thousands, of men?

One night in July 1942, while recovering from malaria on the property of a kind farmer, Yay suddenly encountered a large group of fighters sleeping on the farmer’s property. They were so young, they filled her heart with compassion.

Yet, in the morning, she told them to leave for the safety of the farmer and his family. None of them moved. Yay didn’t yet realize they were hearing the same thing from everyone: leave for our safety. They told Yay they would make no decision without direct orders from someone they referred to as “the major.”

Marking, standing second from right

A short time later, Yay met him. He was Marcos Villa Agustin, known as Marking, a former boxer and bus driver who, when the Japanese first attacked, had worked for the Philippine army, convoying troops to Bataan. After his convoy was cut off, he became a scout for the army. When the Japanese captured him and found an American flag and eagle tattooed across his chest, they arrested him. But he managed to escape into the jungle, where other Filipinos eventually gathered to him, forming a guerrilla band.

Marking and Yay connected immediately. He asked her to join his unit. He understood her physical limitations but was determined to assist her with these as best he could, because he knew that her intelligence—and her typewriter—could be powerful weapons..."

Excerpt from "Yay Panlilio: Guerrilla Writer" from Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater.

Yay Panlilio and Marking

Thursday, June 2, 2016

Letter from American Red Cross staff assistant stationed in Manila

Letter from Faye Anderson, Red Cross staff assistant, sent early July, 1945

Dearest Family:

I am going to try to relate properly the most exciting week of my life so far in the big Red Cross...

Manila, as it is now, is more than I have words to describe. The destruction, starvation, persecution, and ruin is incredible. to say the least. It's a down right crime to have happen to any place what happened here...To put it short, there is literally nothing left of what must have been the most beautiful spot in the world, some buildings dating back to the 1600s. The art, architecture, traditions, etc., that have been lost here will take two generations to regain.

It is all in a state of complete confusion...[but] it's a great thrill to be an American and see how our boys have taken hold, working day and night to further this war...The Filipinos look to us like Gods and can't do enough for us as we are the Yanks that saved them from a fate worse than death. As you pass along the streets, even the half starved [children] make the "V" for victory sign with their fingers, and yell out, "Victory Joe" as every Yank to them is a Joe. We should be very proud of our nation...

This city is filled with tragic stories and it makes you gasp to hear some of them. The Filipinos really suffered and I'm amazed at the way they are able to take it all. Their city in ruins, half starved, their families killed and tortured in front of their eyes. We all don't know how lucky we are to be Americans. I was talking to a charming Filipino woman who evidently came from a very good family and she said they wouldn't have cared if there hadn't been a pillar or post left in the city as long as the Americans arrived..

I will say that the Red Cross is doing one marvelous job here and I'm proud to be in their organization...

My love to You all, Faye

From: We're in This War Too: World War II Letters from American Women in Uniform

Dearest Family:

I am going to try to relate properly the most exciting week of my life so far in the big Red Cross...

Manila, as it is now, is more than I have words to describe. The destruction, starvation, persecution, and ruin is incredible. to say the least. It's a down right crime to have happen to any place what happened here...To put it short, there is literally nothing left of what must have been the most beautiful spot in the world, some buildings dating back to the 1600s. The art, architecture, traditions, etc., that have been lost here will take two generations to regain.

Manila's legislative building, 1945

US troops, Manila, February 27, 1945

This city is filled with tragic stories and it makes you gasp to hear some of them. The Filipinos really suffered and I'm amazed at the way they are able to take it all. Their city in ruins, half starved, their families killed and tortured in front of their eyes. We all don't know how lucky we are to be Americans. I was talking to a charming Filipino woman who evidently came from a very good family and she said they wouldn't have cared if there hadn't been a pillar or post left in the city as long as the Americans arrived..

I will say that the Red Cross is doing one marvelous job here and I'm proud to be in their organization...

My love to You all, Faye

From: We're in This War Too: World War II Letters from American Women in Uniform

Wednesday, June 1, 2016

Endorsements for Women Heroes of World War II: The Pacific Theater

"So meticulously researched and jam-packed with engaging stories of extraordinary women, interwoven with the essential facts of the conflict in the Pacific. What an accomplishment! Kathryn Atwood’s finely detailed and fast-paced writing makes for fascinating

reading, exquisite close-ups of little-known women and a much needed perspective

on World War II. Before the bombing of Pearl Harbor through the long years of

Japanese occupation, women bravely, day by day, stood with the victims of war

and thwarted the enemy. Finally, their stories are told."

--Mary Cronk Farrell, author of Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific

"Anyone who thinks that women's only responsibility in World War II was keeping morale high on the home front will change this view after reading about spies, prisoners of war, guerilla fighters and other courageous women in Kathryn J. Atwood's Women Heroes of World War II. By using their own voices from memoirs, diaries and other sources, Atwood clearly lets us know that valor is not, and never has been, only a men's trait."

--Elizabeth M. Norman author of We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Women Trapped on Bataan

"Atwood's vivid, accessible storytelling brings to life the oft' forgotten female spies, saboteurs, and survivors who were utterly crucial to American victory in World War II. This book rightly solidifies their place in human history."

--Mary Cronk Farrell, author of Pure Grit: How American World War II Nurses Survived Battle and Prison Camp in the Pacific

"Anyone who thinks that women's only responsibility in World War II was keeping morale high on the home front will change this view after reading about spies, prisoners of war, guerilla fighters and other courageous women in Kathryn J. Atwood's Women Heroes of World War II. By using their own voices from memoirs, diaries and other sources, Atwood clearly lets us know that valor is not, and never has been, only a men's trait."

--Elizabeth M. Norman author of We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Women Trapped on Bataan

"Atwood's vivid, accessible storytelling brings to life the oft' forgotten female spies, saboteurs, and survivors who were utterly crucial to American victory in World War II. This book rightly solidifies their place in human history."

--Ben Montgomery, author of Grandma Gatewood's Walk and The Leper Spy: The Story of an Unlikely Hero of World War II.

"Kathryn Atwood presents refreshing perspective into the horrors of the Pacific War through the forgotten stories of heroines, who have mostly been lost in the vast historiography of WWII.

--Jenny Chan, Director at Pacific Atrocities Education.

"Kathryn Atwood presents refreshing perspective into the horrors of the Pacific War through the forgotten stories of heroines, who have mostly been lost in the vast historiography of WWII.

--Jenny Chan, Director at Pacific Atrocities Education.

"Kathryn Atwood’s “Women Heroes of WWII-the Pacific

Theater tells the stories of fifteen gutsy ladies—writers, agents,

activists, nurses, survivors, and others—whose bravery, resilience, and

determination to take risks, confront adversity, and even face death are

revealed from a perspective too often ignored. A modern day Profiles in

Courage."

--David Rensin, co-author

with Louis Zamperini of his autobiography, Devil at My Heels, and his

collection of life lessons, Don’t Give Up, Don’t Give In.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Angelina Trinidad: World War II Filipina Nurse: Liberation!

Everybody was jumping. Some are crying. It was so nice. I even want to remember

it. I always try to remember when the Americans landed in a barrio before

Sibulan, Calo. It is a small coastal barrio with small huts. Fishermen live

there. The Americans landed there. I’m not sure how many, but they landed in

landing barges—two or three. When they open the landing barge, I remember very

well the American soldiers were all in camouflage uniforms. We were there by

the road with the mountains at our back. Juaning Dominado, the husband of Tita Gras is

the one who instructed the Americans whether to bomb because they were bombing

the mountains because it was the Japanese that were in the mountains now and

the guerrillas are down from the mountains already! So he instructs where—to

the left, to the right. So we were there beside him and we can see and hear. We

saw the Americans came wading in the sea.

I did not see any Japanese

anymore after that. After we left for the mountains, I never saw any Japanese

any more. When we were up in the mountains, the guerrillas were always

watching. They would ambush the Japanese that would come near. There is always

a small fight between the guerrillas and the Japanese, but I never saw them.

After they landed and we were

able to go back to the house, everyone came to the Big House. We had lots and

lots of American officers in the house because Tita Belen was very friendly. They

always made parties.

Angelina Trinidad Locsin, now 96, lives in Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, The Philippines, with her two daughters, Maria Teresa and Maria Trinidad, and their husbands. Benjamin, who she married on March 1, 1944, died in 1997. So did her only son, Ramon Tomas, in July 2015. Angelina's four grandchildren, three sons-in-law and eight great grandchildren live in the Chicago, Illinois area.

Her incredible memory continues to amaze family and friends!

Angelina, July, 2012, looking through the letters Benjamin sent her while he was imprisoned by the Japanese

Angelina Trinidad Locsin, now 96, lives in Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, The Philippines, with her two daughters, Maria Teresa and Maria Trinidad, and their husbands. Benjamin, who she married on March 1, 1944, died in 1997. So did her only son, Ramon Tomas, in July 2015. Angelina's four grandchildren, three sons-in-law and eight great grandchildren live in the Chicago, Illinois area.

Her incredible memory continues to amaze family and friends!

Angelina Trinidad: World War II Filipina Nurse: Into the Mountains

Benjamin was released in 1943. He started working in Santiago hospital in Manila and worked there for a while. That was all rice field then. It was the only building there that catered to the Spanish community. And then Benjamin had to go home to bring medicine for his father, Vicente Locsin.

Benjamin and I got married in 1944. Then we went home to Dumaguete. There were so many Japanese sentries there. You had to bow to them and smile. Vicente was getting very worried because the Japanese army was taking lots of professionals for questioning and they never came back. So he was scared that they will take his son.

It was only when we came home to Dumaguete and there were lots of Japanese coming to the house because Vicente befriended the Japanese because he did not want the Japanese to be against us. So when we came and they saw that Benjamin was a doctor, they got close to us when somebody was sick. They would call us and they would stay and make kwento (chat).

Benjamin's sister, Gracia Dominado, lived in a house across from us. She played the piano, so when the Japanese would come, they would call her to play for them. The Japanese officers knew all the classical music. They would tell her, “you play Hungarian Rhapsody.” They were very educated and were really gentlemen. I have no bad thoughts about the Japanese that I came in contact with. They were all educated, respectful. But the lower-class, not the officers—the enlisted men they call “low class,” they were the ones that abuse and kill and torture.

I was scared only when they began picking up prominent men like men who worked in the hospital or were engineers or in the treasury before the war. The Japanese picked them up for questioning and then they never come out again, are never seen, and many were executed. One time there was a friend of Benjamin's. I don’t remember his name. He was like mestizo (Spanish blood mix). We had a small clinic with Benjamin downstairs. That’s where we talked with him and we made stories with him. One time when he was going out already, the Japanese came and told him to go with them, and we never saw him again. That was the time when I got scared.

So when Vicente said, “I think it’s high time that you go to the mountains because I think the Japanese are getting suspicious.” That was the time we went. We arrived here after we were married in maybe late April and we went to Zamboanguita by boat in September. So it was 5 months were were here in Dumaguete. After that, we stayed in Zamboanguita for 2 days and then were taken up to the mountains by the runners of the guerrillas.

I enjoyed it there [in the mountains] because I was

playing mah-jong every day! That’s where I learned really how to play mah-jong.

There were 3 families that stayed together: the Dominados the Aviolas, and the Montebons. That’s why we call the place, “Do-Al-Bon.”

That was a famous place before. The families of those guerrilla officers lived

together in like a long barracks. They divided it into 3 compartments—one space

for the Dominados, Aviolas, and Montebons. It was decorated with sawali–very native—and each compartment has a stairs, so it’s private really, you’re

not together. But every morning after breakfast we start playing mahjong

already. The wife of Montebon, Aviola, and Dominado are all mahjong players so

they taught me how to play. So it was not scary for me at all.

I was living in the mountains, but Benjamin was asked if he would work. Major Dominado was very powerful, so when he asked Benjamin if he wanted to work, he said, “yes, I want to work. I want to help in the clinic up in the mountains." That was 1 1/2 hours walk from our house at Do-Al-Ban to the clinic. Benjamin stayed in the clinic. I would go and visit him at the clinic once in a while. But we would rest. There were small huts in the mountains. And you know the old people there did not know we were at war! They were saying, “why are you in the mountains?” We told them we escaped Dumaguete because there were lots of Japanese already there because we are at war. They would say, “why?” They remember only the owner of a Japanese store we had here and they didn’t know (why we are at war with him)!

Next: Liberation!

I was living in the mountains, but Benjamin was asked if he would work. Major Dominado was very powerful, so when he asked Benjamin if he wanted to work, he said, “yes, I want to work. I want to help in the clinic up in the mountains." That was 1 1/2 hours walk from our house at Do-Al-Ban to the clinic. Benjamin stayed in the clinic. I would go and visit him at the clinic once in a while. But we would rest. There were small huts in the mountains. And you know the old people there did not know we were at war! They were saying, “why are you in the mountains?” We told them we escaped Dumaguete because there were lots of Japanese already there because we are at war. They would say, “why?” They remember only the owner of a Japanese store we had here and they didn’t know (why we are at war with him)!

Next: Liberation!

Angelina Trinidad: World War II Filipina Nurse: War and Occupation

The following are the recollections of Angelina Trinidad Locsin, witness to war in the Philippines.

There was commotion and confusion. Our nuns who ran the hospital were all Americans and Canadians. We were all crying. Dr. Davies told us that the hospital is being commandeered by the US Army. We were inducted in the USAFE January 13, 1942. Most of the hospital employees—doctors, nurses, technicians, and workers--were inducted into the US Army. We all boarded a boat and were brought to Mindanao where we set up theArmy Force

Hospital

We had dug-out foxholes around the hospital. That’s where we all jumped when we heard the sirens because the planes were coming near to bomb. So when we hear that we all run out of the hospital and jump in foxholes. I was scared that time. If we are working on a patient, we just leave them. There were assigned boys to stay and stand watching in each ward. We had 4 or 5 quonset huts: one for surgical patients, one for medical, one for the emotional like shell-shocked and depressed, and then we had one for operating room. We took rotations. I would work in surgical and then medical and then psych ward. We had to work there even though it wasn’t ready. We improvised.

The most scary part of the war was when I saw my first casualty. I think he was hit at the back. We could see his lungs breathing.

We worked in the hospital until we surrendered to the Japanese. After the surrender, they took all the Americans out. I don’t know where they brought them. There were only Filipinos left. And then we didn’t have Japanese patients yet, only Japanese officers coming around.

But then in even not a month, they closed the hospital and brought all the nurses to Bukidnon and made us work in the civilian hospital of that town. And the Filipino men [including a young doctor named Benjamin Locsin with whom Angelina had fallen in love] were brought to a concentration camp near Bukidnon. They were just interned there. And then when the Japanese decided to bring us back toManila ,

they loaded us the ones from Luzon .

Benjamin wrote me letters because they had a small cantine in the camp, and some girls sold food and toilet articles there. And Benjamin befriended some of the girls and said, “can I send letters with you?” But it was risky. One time it was not the girls that got caught: one of the boys who worked “detail” at the camp (they call it detail if you are made to work at the camp by the Japanese). He was caught with letters from people outside. He was punished. They were afraid they will kill him but they didn’t. He was just punished. I don’t know how they did it. But the girls were never inspected so Benjamin smuggled his letters through the girls. There were days that the girls go to the camp maybe three times a week and Benjamin already had letters prepared for them to bring to me.

Angelina Trinidad

I grew up when the Philippines Negros Island

Angelina Trinidad (left) with the rest of her graduating class

I was 22 years old and had been was working as a nurse just

6 months when war was declared on December 8 1941. I remember this very well

because it was Feast of the Immaculate Conception. We all heard mass and when

we came out of the chapel, Dr. Davies, our Medical Director was by the door

with three American Army officers. They announced, “We are at war! The Japanese

bombed Pearl Harbor !”

There was commotion and confusion. Our nuns who ran the hospital were all Americans and Canadians. We were all crying. Dr. Davies told us that the hospital is being commandeered by the US Army. We were inducted in the USAFE January 13, 1942. Most of the hospital employees—doctors, nurses, technicians, and workers--were inducted into the US Army. We all boarded a boat and were brought to Mindanao where we set up the

We had dug-out foxholes around the hospital. That’s where we all jumped when we heard the sirens because the planes were coming near to bomb. So when we hear that we all run out of the hospital and jump in foxholes. I was scared that time. If we are working on a patient, we just leave them. There were assigned boys to stay and stand watching in each ward. We had 4 or 5 quonset huts: one for surgical patients, one for medical, one for the emotional like shell-shocked and depressed, and then we had one for operating room. We took rotations. I would work in surgical and then medical and then psych ward. We had to work there even though it wasn’t ready. We improvised.

The most scary part of the war was when I saw my first casualty. I think he was hit at the back. We could see his lungs breathing.

We worked in the hospital until we surrendered to the Japanese. After the surrender, they took all the Americans out. I don’t know where they brought them. There were only Filipinos left. And then we didn’t have Japanese patients yet, only Japanese officers coming around.

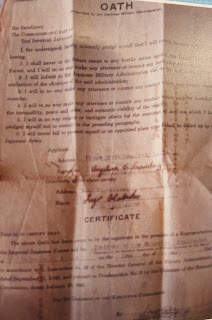

The oath of allegiance the Japanese made Angelina sign

But then in even not a month, they closed the hospital and brought all the nurses to Bukidnon and made us work in the civilian hospital of that town. And the Filipino men [including a young doctor named Benjamin Locsin with whom Angelina had fallen in love] were brought to a concentration camp near Bukidnon. They were just interned there. And then when the Japanese decided to bring us back to

Benjamin wrote me letters because they had a small cantine in the camp, and some girls sold food and toilet articles there. And Benjamin befriended some of the girls and said, “can I send letters with you?” But it was risky. One time it was not the girls that got caught: one of the boys who worked “detail” at the camp (they call it detail if you are made to work at the camp by the Japanese). He was caught with letters from people outside. He was punished. They were afraid they will kill him but they didn’t. He was just punished. I don’t know how they did it. But the girls were never inspected so Benjamin smuggled his letters through the girls. There were days that the girls go to the camp maybe three times a week and Benjamin already had letters prepared for them to bring to me.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

Footage of Jane Kendeigh, the first navy flight nurse to land on Iwo Jima

I was quite thrilled to receive the following link featuring an eight-minute video of rescue on Iwo Jima. I've seen B&W photos of Jane Kendeigh, the first navy flight nurse to land on Iwo Jima, a woman whose story is included in the book, but seeing her in action is quite startling.

Jane is seen at the seven-minute mark: http://bit.ly/1Yvmgy8

Jane is seen at the seven-minute mark: http://bit.ly/1Yvmgy8

Sunday, February 28, 2016

The Bataan nurses on their way to Corregidor, as seen by Carlos P. Romulo, Press Officer to General MacArthur

"There were cars filled with nurses, and I could not bear to look into their faces as we passed on that crowded road. I knew what was written on them. I had seen it in the underground hospital at Corregidor, in the open and unprotected tent hospitals on Bataan. It was not fear. I never saw a nurse afraid. It was something more dreadful than fear, because that is active. It was inevitability.

They knew that the savage juggernaut was rolling at their heels. They knew what to expect. They had seen what hate can do, when their hospitals were deliberately bombed and wounded men screamed in the last agony under the Japanese planes. They had heard stories of other women...

They were fleeing toward the water line, where there might or might not be boats to carry them to Corregidor. And there was no place for them to hide on Corregidor...

I will never forget the faces of those girls. I will never forgive the fact that American women, under the American flag, had to know that night--the last night on Bataan."

Excerpt from I Saw the Fall of the Philippines by Colonel Carlos P. Romulo, Pulitzer Prize winner and personal aide to General Douglas MacArthur.

They knew that the savage juggernaut was rolling at their heels. They knew what to expect. They had seen what hate can do, when their hospitals were deliberately bombed and wounded men screamed in the last agony under the Japanese planes. They had heard stories of other women...

They were fleeing toward the water line, where there might or might not be boats to carry them to Corregidor. And there was no place for them to hide on Corregidor...

I will never forget the faces of those girls. I will never forgive the fact that American women, under the American flag, had to know that night--the last night on Bataan."

Excerpt from I Saw the Fall of the Philippines by Colonel Carlos P. Romulo, Pulitzer Prize winner and personal aide to General Douglas MacArthur.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)